Taming of the Smoky Hill River

How the titanic battle between Man and nature created present-day Salina

GET THE CITIZEN JOURNAL APP - FREE!

Guided by humans, assisted by AI

In the heart of Salina, Kansas, a dry, neglected channel winds through the city's core—a ghost of what was once the vigorous Smoky Hill River. For decades, this abandoned riverbed has remained largely forgotten, cut off from the waterway that gave birth to this prairie community. Now, after years of planning and advocacy, Salina stands at the threshold of a renaissance as it embarks on an ambitious river renewal project to reconnect with its riverine heritage. The Friends of the River Foundation sees this project as bringing back more than just water—they're working to restore the soul of the city.

This ambitious project represents the latest chapter in a centuries-long relationship between the Smoky Hill River and human civilization—a story of sustenance, destruction, conquest, and now, reconciliation.

Long before European contact, the river valley served as prime hunting grounds for Plains tribes who followed bison herds along its 575-mile course. The watershed, spanning nearly 58,000 square miles, teemed with wildlife that sustained indigenous communities for generations.

European eyes first beheld the Smoky Hill in 1541 when Spanish conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado marched north in search of the fabled Quivira. Later, in 1806, American explorer Zebulon Pike (of Pike's Peak fame) identified it as the main southern branch of the Kansas River.

The river's strategic importance grew dramatically after the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 opened the region to U.S. settlement. When gold was discovered near Pike's Peak in 1858, an old Native American trail along the Smoky Hill provided the shortest route west from the Missouri River. Thousands of fortune-seekers braved this dangerous path, triggering violent conflicts with indigenous peoples defending their ancestral lands.

The U.S. Army established frontier forts like Fort Hays to secure the route, and by the late 1860s, the Kansas Pacific Railway had pushed through, making the overland trail obsolete. By 1870, the valley was under full U.S. control, with new farms and towns—including a growing Salina—dotting the landscape.

Settlers harnessed the river's power and Salina prospered as a agricultural hub. The city's first watermill, built in the 1860s, marked the birth of a flour-milling industry that, leveraging local railroads, would eventually make Salina the third-largest flour-producing center globally by the early 20th century.

But the river that gave life also brought destruction. Catastrophic floods in 1903, 1915, 1938, and 1941 repeatedly devastated farms and neighborhoods. After each disaster, residents rebuilt, but patience wore thin.

Old-timers still talk about the '38 flood that wiped out bridges and homes. After each disaster, there were growing calls for action as residents insisted something had to be done.

Kanopolis Dam construction

The response came in stages. Congress authorized a flood-control project in 1940, leading to the completion of Kanopolis Dam in 1948—the first large flood-control lake in Kansas. Despite this measure, the Great Flood of 1951 overwhelmed the system, leaving much of Salina underwater.

That disaster prompted a radical solution: In 1957, the Army Corps of Engineers began rerouting the Smoky Hill around Salina through a straight diversion channel. The project, completed in 1961, effectively cut off the natural riverbed that wound through downtown.

The engineering feat achieved its purpose—Salina has not suffered catestrophic flooding since (major flooding in 1993 did not match earlier disasters) . But as the abandoned channel through town stagnated, residents gradually realized something precious had been lost.

The community had protected itself from the river, but in the process, divorced itself from it. For generations, children grew up not even knowing there was a river in town.

Periodic proposals to rehabilitate the channel emerged—a 1978 city study, a 1986 citizen vision process—but gained little traction. Finally, in 2007, local advocates formed the Friends of the River Foundation, dedicated to reviving the dry channel.

The resulting Smoky Hill River Renewal Master Plan, approved in 2010, envisioned dredging accumulated silt, reestablishing flow, restoring habitat, and creating recreational amenities along the old course. In recent years, the city secured funding, including a sales tax measure passed in 2016, to begin implementation.

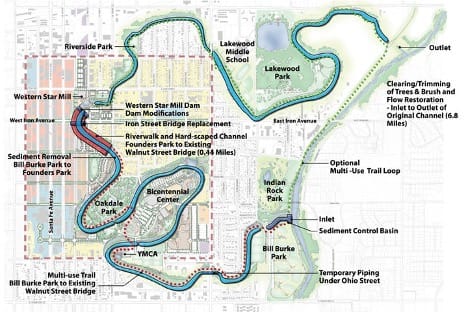

Smoky Hill River Channel’s path through Salina, engineering elements required to restore and maintain flow, potential riverside trail systems, and the proposed downtown riverwalk placement.[i]

Today, as engineers design water control structures, Salina stands at the threshold of reconnecting with its river heritage. The project promises not just aesthetic improvements but economic revitalization—waterfront dining, kayaking, fishing, and river walks that could transform downtown.

The restoration effort represents a full circle moment. For centuries, human civilization here has tried to either live with the river or control it. Now the community is learning to do both—respect its power while embracing its presence.

As Salina works to restore the Smoky Hill's flow through its heart, the project embodies a wider cultural shift: from conquering nature to coexisting with it. The river that shaped this community's past now flows toward its future—tamed, but no longer forgotten.

[i] https://smokyhillriver.org/project-scope/

SUBSCRIBE ONLINE TO GET THE SALINA CITIZEN JOURNAL IN YOUR INBOX - FREE!

Sponsors (click me!)