Let’s talk tariffs

An economic turning point in the 80-year history since WW2. But will they work?

Key takeaways

· Donald Trump campaigned on and now has the electoral mandate to attempt to use tariffs to rebuild moribund US manufacturing.

· Tariffs impose a tax on foreign imports to make domestic industry more competitive.

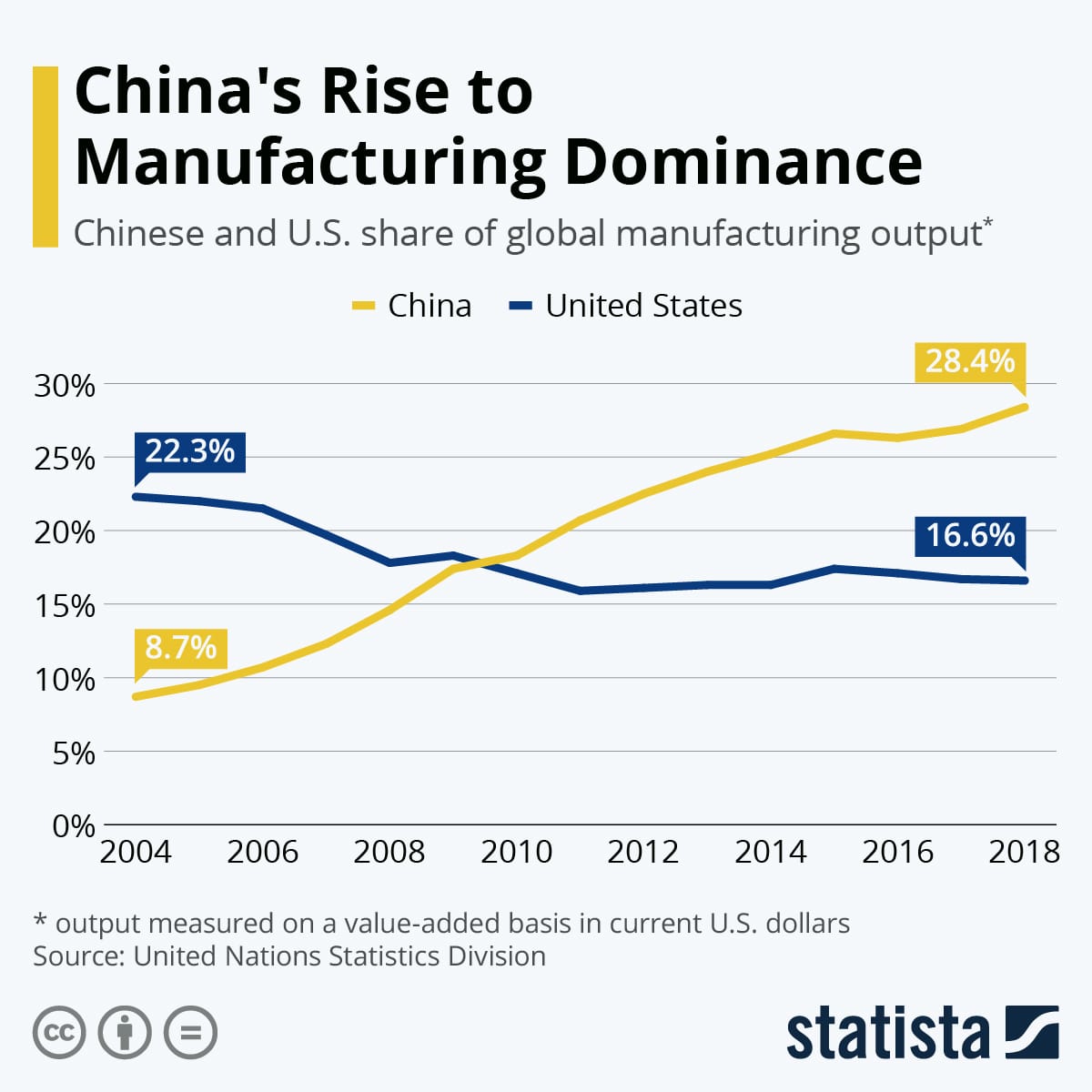

· America’s global manufacturing share in 1940 was 50%. Today it’s just 16%.

· Free trade has reigned for the last 5 decades and hollowed out America’s industrial heart.

· Higher prices could derail the tariff experiment before new industries can take root.

· America must focus on critical goods like medical supplies and defense while accepting some imports.

Donald Trump ran and won on the promise to restore American manufacturing. His signature economic tool for doing so are tariffs and he has wasted no time implementing them, posting on his social media platform that he will impose tariffs on China, Mexico, and Canada. Tariffs, the imposition of a tax on foreign imports to make domestic industry more competitive, are not new to America (they were in place for much of the 19th and early twentieth centuries), but they are new to the modern economy. There is not much evenhanded discussion about tariffs out there. They are either very bad (mainstream media, academia) or will succeed bigly (MAGA). This article seeks to be a balanced discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of tariffs, which through his rhetoric and personnel appointments, Trump is going to enact.

The need to have a domestic manufacturing economy is illustrated by America’s experience in WW2. On the eve of war in 1940, America accounted for about 50% of all global manufacturing output. The US quickly converted this massive civilian manufacturing industry into wartime production. In 1940, America produced about 330 tanks, 6,000 aircraft, and 200 ships per year. By the peak of the war in 1944, America was producing 17,500 tanks, 96,000 aircraft, and 2,500 ships per year, dwarfing all allies and opponents.

In 2024, America has far less civilian manufacturing capacity. Americas share of global manufacturing capacity is around 16% versus China’s nearly 30%, a much bigger absolute capacity than America’s 50% in 1940 due to the growth of the global economy. Chinese shipyard capacity is 232 times America’s[i]. The need to reindustrialize is clear if America wants to remain a great power, but before we can answer if tariffs will get us there, we need to start the story immediately after America’s WW2 triumph.

WW2 aftermath

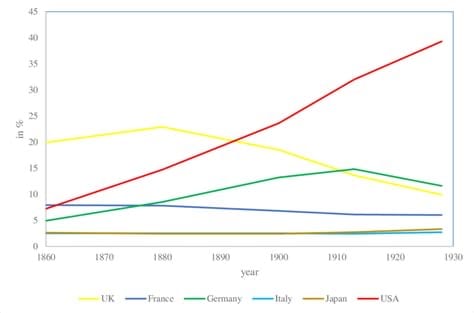

During the Industrial Revolution in the late-19th century through WW2 in the 20th century, America became the workshop of the world as it grew its share of global manufactured goods output to nearly 50%.

After the war, the Soviet Union became the United States’ chief rival almost as soon as Germany and Japan were defeated. To wage the Cold War, the US created a global network of allied countries - often referred to as the Free World. To create this network, the US essentially bought off countries by offering them access to its massive consumer market on free trade terms. The US would also guarantee this free trade with is powerful military, notably maintaining freedom of the seas with the US Navy.

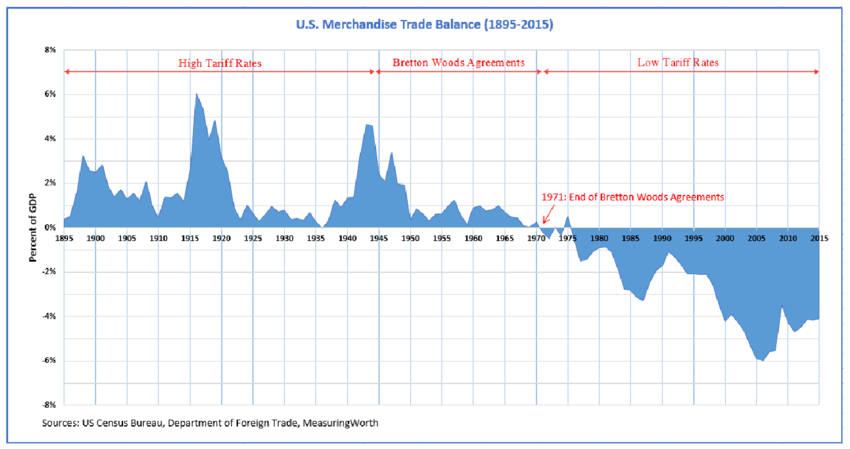

The US enshrined this system with the Bretton Woods Agreement, which linked the dollar to gold and pegged all other currencies to the US dollar, establishing it as the reserve currency of the world. This system worked well for a time as America coasted on its massive domestic manufacturing base.

The Nixon Shock

In the 1960s, America spent massively on the Vietnam War and LBJs Great Society social programs (“guns and butter”). This created inflation and put pressure on the US dollar’s peg to gold. Additionally, parts of the rest of the world, notably Germany and Japan, developed their own large manufacturing bases and exported goods into the American market on free trade terms. When America bought foreign goods, it sent US dollars abroad to other countries. Other countries began to doubt the credibility of the dollar and converted their dollars to gold. Gold was rushing out of the US so fast that running out of gold, and a financial crisis, was likely. Nixon had no choice but to end US dollar convertibility to gold in 1971, ushering in the free trade era that lasted 50 years until Donald Trump’s election in 2024.

Hollowing out of America

Its important to note that the Free World alliance system worked and the US won the Cold War without firing a shot in 1991. However, this system also ripped out the industrial heart of America, and is responsible for many of the themes you’re familiar with here on Ad Astra: deindustrialization, deaths of despair, brain drain, inequality, the list goes on.

The post-Nixon Shock system in the 5 decades after 1971 allowed the US to run larger and larger trade deficits with the rest of the world. In this system, the US would buy cheap goods from offshore, where labor costs, environmental regulations, etc. were more favorable, and send dollars abroad to pay for them. This money came from issuing debt.

This system incentivized manufacturers to offshore their factories, and after 50 years, America lacks both industry and the knowhow to make things. When a firm offshores its manufacturing, it loses the ability to make things by losing routine interactions between its designers and actual manufacturing processes, even if it retains the “knowledge work” in America. They key to the US mobilizing so quickly to win WW2 was already having a massive civilian manufacturing economy.

Many countries took advantage of the US-led “free-trade system” after 1971, which made their domestic industry more competitive than the US’ own industry. For example, Japan nurtured its automotive and electronics industries through subsidies and favorable loans to companies like Toyota and Sony. By exporting high-quality, fuel-efficient cars and competitive electronics, Japanese firms gained significant US market share, challenging American manufacturers. There are other similar examples in Germany, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, India, and notably, China.

After the end of the Cold War, entry into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which enhanced free trade with Mexico and Canada, and welcoming China into the World Trade Organization (WTO), accelerated the decline of American manufacturing. Donald Trump was elected in 2024 with the mandate to reverse these trends by applying tariffs. Will it work?

Will tariffs work?

The US has a long history of successfully using tariffs to protect domestic industry, notably at the urging of Alexander Hamilton. But it’s not the 19th century anymore and can you really close off your industry in the 21st century, connected world?

The chief, legitimate, risk of imposing tariffs is raising the price of US consumer goods – inflation. If consumers face higher costs in the short- to medium-term, before domestic industry can develop, will voters end the tariffs experiment at the ballot box? It is certainly possible.

The success case for tariffs, where America redevelops significant domestic manufacturing capacity that can compete globally, will probably include lots of robots and automation, not a return of all the lost manufacturing jobs and unions. Relatively expensive US labor cannot and should not compete with cheap foreign labor.

Ultimately, the success of tariffs is uncertain and will depend on: 1) how much inflation is generated, 2) how many new or better jobs are created and 3) how much “pain” the voting public is willing to bear in terms of higher prices to Buy American.

My own two cents, as an American, is that we should be strategic about what we onshore. Its ok for cheap toys to be imported from Asia but we should make things like national security critical goods and medical supplies here in the US. I’ve laid out my vision for a new global trading system and US industrial policy in prior articles.

The soon-to-be-implemented tariffs represent a critical juncture in America’s economic trajectory. Will tariffs revitalize domestic manufacturing, restore strategic industries, and bolster national security, or will they merely trigger inflation and alienate voters? History suggests that America thrives when it builds, innovates, and invests in its people and industries. However, success in a 21st-century global economy will require more than just protectionist policies—it will demand strategic foresight, automation, and targeted investments to rebuild critical capacities while maintaining global competitiveness. Whether tariffs are the right tool or just a stopgap remains to be seen, but one thing is clear: the decisions made now will shape America’s economic destiny for decades to come.

[i] https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/china%E2%80%99s-shipbuilding-capacity-232-times-greater-united-states-212736#:~:text=%22China's%20shipbuilding%20capacity%20is%20232,just%20take%20it%20from%20me